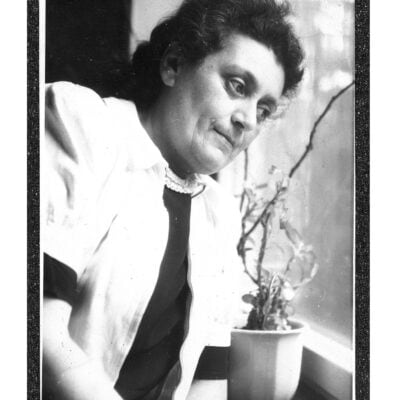

In flight from the Nazis since Hitler’s rise to power in 1933 , Helene Ehrlich was used to moving fast, but rarely, if ever, on skis. Now, at age forty-two, she was struggling to keep up with her much younger traveling partner as they zigzagged through the snow-filled forest on the Norway-Sweden border.

This was no vacation. The snow in places was often too deep and thick for skiing, and the temperature nearly thirty degrees below zero. It was April 1941, a year after the Nazis had invaded Norway. Ehrlich, a German Jewish refugee working for the Norwegian resistance in Oslo, was fleeing the Gestapo and skiing for her life.

When she sat down to rest, one of her skis began slipping down the hill. Although she lunged for it, the ski was gone, and Ehrlich was now certain her long, tortuous odyssey as a stateless Jewish refugee would come to an end in a Nazi jail cell, or on the gallows.

As her partner skied on to the top of the mountain without her, Ehrlich sat exhausted and bewildered in the snow. She had every reason to think she would never see her children again.

She remembered them now, crying and holding hands, not wanting to part from her, on that morning in Prague two and a half years earlier, on November 27, 1938. Having arrived in Prague from Nuremberg in 1933 without documents or money, Ehrlich had labored at the most menial jobs in order to support the twins and to obtain transportation and visas. Finally, in the last frantic days before Hitler moved into Czechoslovakia, visas had arrived from the United States—but only for the children.

At the last possible moment, through the intervention of the local Jewish community and the Norwegian humanitarian organization Nansenhjelpen, she became one of twenty-six people to whom the Norwegian consulate issued a “Nansen” passport for stateless people. With only one suitcase and a picture of her children, Helene Ehrlich arrived in Oslo.

There, those who had been persecuted were housed, fed, and even feted by Norwegian officials. Ehrlich cleaned the ceilings and walls of the king of Norway’s palace, and her gratitude was boundless. Full of hope, she went to the United

States consulate, determined to secure permission to go to America to join her children; she was turned down. She then tried to stow away on a Norwegian ship bound for America but was discovered.

Then, on April 9, 1940, barely more than a year since she had escaped them in Czechoslovakia, the Nazis violated Norway’s announced neutrality and occupied the country. As German tanks pushed through the streets of Oslo, Ehrlich made a fateful decision: she had had enough of fleeing. She would honor and repay the Norwegians by joining their underground.

Within days of the occupation, she found a job as a cleaning woman in a building housing German military per sonnel. As she moved from office to office-with her pail and broom, to all the world a simple cleaning lady-she memorized documents left on desktops. By now she was fluent in Norwegian, and the Nazis did not suspect that German was her native language. She committed to memory fragments of the officers’ conversations. Regularly, she reported the information to her contacts in the Norwegian resistance.

The dangerous work went well for a year, but then the Germans, who were now secretly planning the invasion of Russia for June 1941, tightened their security. Ehrlich suspected she was about to be discovered, which would mean torture and death.

By another inexplicable stroke of luck, a German officer approached her as they were riding the elevator alone. “You must disappear,” he said. “The Gestapo knows who you are.”

She reported this to her underground group leader and then went into hiding. Many Norwegians, struggling to get to England through Sweden to join the government-in-exile there, had already frozen to death on the border. Increasingly, Norwegian Jews and Jewish refugees such as Ehrlich were being arrested and deported. The resistance would have to find an inventive way to get her across the border. They recruited a guide and another woman: the ruse would be three girls having a lovely time on a skiing vacation.

Only now the “vacation” had turned into a nightmare, and Ehrlich was lost, without her ski, somewhere in the forbidden three-mile zone separating the two borders. Suddenly, her partner reappeared and was heading down the hill toward her—not to retrieve her but to shout in panic, “Run, the Germans are coming!”

Within seconds, two soldiers were pointing their rifles at Ehrlich’s head, and she fainted . When she revived, she found her captors to be not Germans, but landfiskales, Swedish officials collaborating with the Germans and the puppet government of Norway. While her traveling partner, a Norwegian citizen, was allowed to cross the border and to take the train to Stockholm, Ehrlich—stateless, Jewish, and a refugee—was detained and interrogated. Refusing to reveal anything about her underground contacts or the route they had taken, she was thrown in jail. Exhausted, she was sent by the landfiskales back into the forest on the Swedish side of the border where she had been apprehended—there to face, as many others had before her, a painful death from exposure.

After some hours, the jail’s warden and his wife—who opposed the collaborationists—rescued Ehrlich. They brought her to their home and nursed her slowly back to health. They became her advocates, appealing to the landfiskales to permit her to remain in Sweden. Intervention, ultimately through King Gustaf of Sweden, led her to freedom from custody and to a train ticket to Stockholm.

Once again in a strange country, with another language she did not speak, she sustained her self with the hope of reuniting with her children. Yet the danger had by no means passed. Unlike Norway, Sweden, though technically neutral, tipped toward Germany and allowed German troop trains to pass through its territory. Ehrlich joined with protesting Swedish humanitarian organizations, but she had to watch herself even though the war was nearing its end.

The war was over for more than a year before Ehrlich was able to secure a visa and transportation to the United States—on a coal freighter. It had been eight years since she had seen her children. When her twins—no longer small children—greeted her at the dock, she had with her the old wooden skis. The Swedish police had retrieved the one that was lost, so that she could ski out of the woods in their custody. The skis were by now very worn, the leather straps were frayed, and the hemp bindings threadbare, but they were the skis that had carried her to freedom.