A 1924 Yiddish-language cookbook found in the Museum’s Permanent Collection recalls the golden age of Jell-O, when average Americans clambered for an easy, affordable way to serve luxury dishes. It also recalls the major halachic law debate that ensued when Jell-O initially released its product.

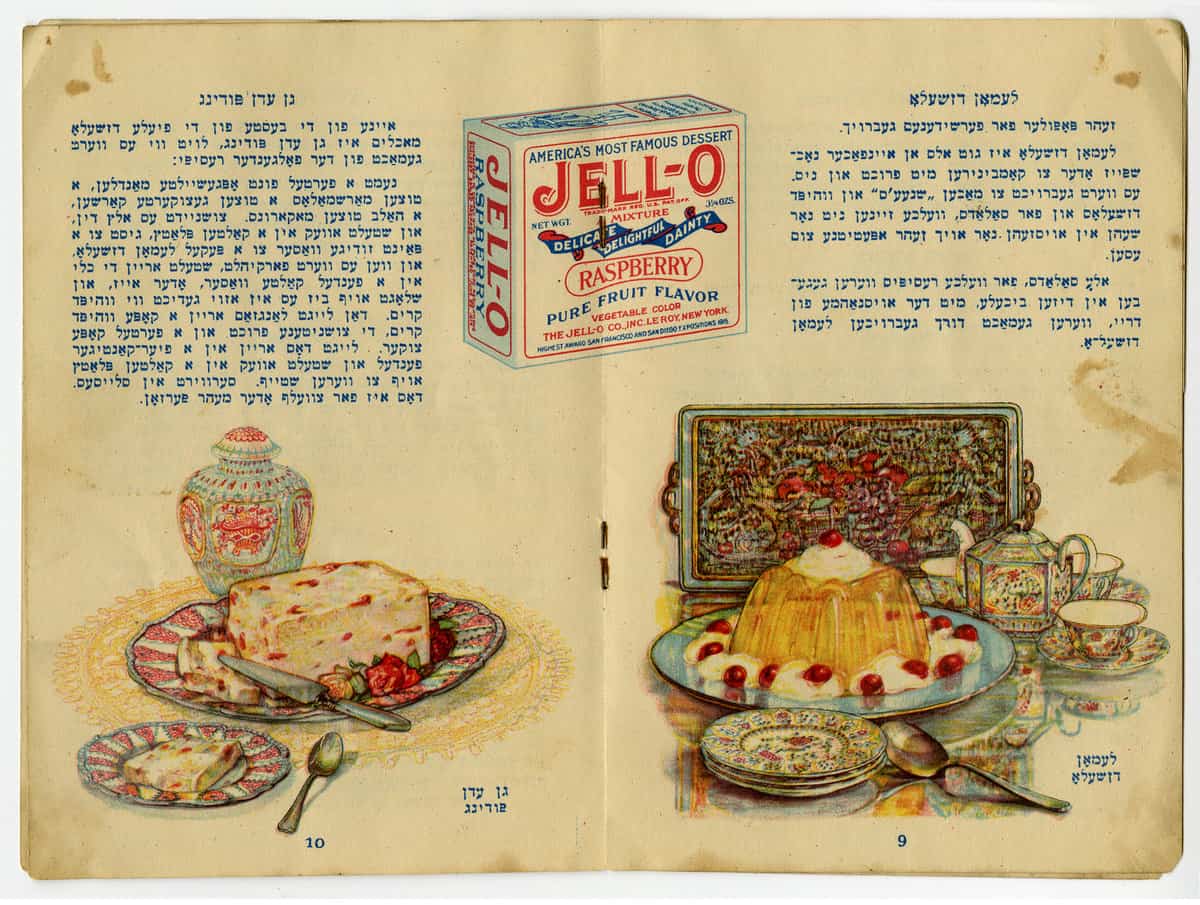

The Jell-O Co. cookbook features beautiful colorful illustrations by the artist Angus Mcdonald. The picturesque scenes of happy, rosy children grabbing at Jell-O products belie the tremendous changes happening in middle class American homes and the rapid pace of assimilation among recent Jewish American immigrants.

An Everyman Luxury

Since the Middle Ages, gelatin molds had been a luxury, served only in the wealthiest European and American homes. The necessary process of rendering and clarifying collagen from animal bones was labor intensive and required a kitchen staff, which only members of the upper class could boast. Obtaining enough animal bones for gelatin was also prohibitively expensive for most.

Only nineteenth century industrialization shifted the status quo. The first essential figure in the popularization of Jell-O was Peter Cooper, a Renaissance man whose other innovations addressed issues in railroad locomotion, canal boats, fire proof buildings, and aviation, to name a few. Cooper created a recipe for “portable gelatin,” a less flavorful predecessor to Jell-O.

In 1895, Pearle B. Wait, the owner of a struggling drugstore in LeRoy, New York purchased Cooper’s patent. Influenced by their cough syrup business, he and his wife May Wait began stirring various sugars into the gelatin product. May named their final creation Jell-O, and Pearle attained the patent for it in 1897. The Waits sold their patent to Orator Francis Woodward on September 9, 1899, for a healthy sum of $450.00, but the production of Jell-O remained in LeRoy, New York. After years of struggling to market the product, Woodward nearly lost hope and offered to sell the patent for a measly $35 to an employee of his. Fortunately for Woodward, the sale never went through. Jell-O would go on to earn one million in sales within the next decade.

It took an aggressive marketing campaign, centered on the joys that Jell-O could bring to the American child, to make this success possible. This cookbook, illustrated by Angus McDonald, is a prime example of the Jell-O Co.’s strategy in the early 20th century.

Like many of the earliest illustrations for the Jell-O Co., McDonald’s artwork invokes an ideal American childhood, per the Jell-O Co.’s vision. A small, rosy child in crisp white clothes reaches for a Jell-O box, gift wrapped with ribbon. The scene unfolds in a comfortable middle class home filled with such clutter as clocks, candelabras, and ironing boards. The messaging is clear: Jell-O puts the American dream at your family’s fingertips.

As a commercial illustrator for Jell-O Co., McDonald was in good company. The Jell-O Company also commissioned such highly esteemed artists as Rose O’Neill, Maxfield Parrish, Coles Phillips, Norman Rockwell, and Linn Ball. Their directive was to enchant American consumers. Some of Rockwell’s most enduring illustrations for Jell-O circulated in 1924, the same year as this cookbook and bear many similarities to McDonell’s style and subject matter.

The Great Jewish Jell-O Debate

This Yiddish language edition of a Jell-O Co. recipe book shows a concerted effort by Jell-O Co. to attract Jewish customers. In the late 19th and early 20th century, millions of Jews had immigrated to the United States from Europe to escape the rise of poverty and pogroms in their home countries. They were a large market, and many of them were receptive to commercial American products. They too dreamt of the middle class luxury that Jell-O Co. promised.

Thus arose the great Jewish Jell-O debate. Traditionally, gelatin is made from the bones and hides of animals. The most serious questions Jewish consumers asked were whether Jell-O contained pork products and if those pork products made Jell-O unsuitable for the Jewish kitchen.

A great halachic debate arose, in which many of the greatest 20th century Orthodox rabbis participated. Some argued the gelatin was ponim chadashos (new face). They claimed the manufacturing process so utterly transformed the ingredients that they no longer constituted pork. Their conclusion was that Jell-O was kosher.

Indeed, Jell-O Co. vigorously marketed its products to the Jewish community. In the 1920s, the company worked with the famous advertising firm founded by Joseph Jacobs. Jacobs’ firm specialized in reaching Jewish markets and Yiddish-speaking customers, having already worked on a number of major campaigns geared towards Jewish markets including Proctor & Gamble’s Crisco campaign. Under Jacobs’ guidance, Jell-O Co. sponsored Yiddish-language radio programs that complement this Yiddish-language cookbook.

Some Orthodox rabbis pushed back against Jell-O again in the 1950s. Their concerns can be read as a complaint not only against Jell-O’s ingredients but against the massive cultural changes wrought by food mechanization and rising Jewish assimilation in the U.S. However, the Conservative Rabbinical Assembly certified the claim that gelatin is kosher in 1969.

Ultimately, Jell-O transformed the American kitchen. While it may not be a staple in kitchens today, the product defined this country’s cuisine for decades. It was an innovation for the middle class, promising not only a sweet treat but an idealistic vision of American family life that Americans of all backgrounds, including kosher Jews, came to embrace.