In 1945, Dwight D. Eisenhower, then the Supreme commander of Allied Forces in Western Europe, made sure to personally visit concentration camps so he could give firsthand evidence of the atrocities committed by the Third Reich. Eisenhower also insisted that US troops photograph and film what was left in the camps so that future generations would understand what had happened in the hopes it would never again be repeated.

Of course the liberators – the term used for troops who liberated the concentration camps – who weren’t directed to document the horrors around them were also important eyewitnesses to what occurred. Many came back scarred from what they had seen and didn’t speak of it for years – or ever. Some brought back objects from their service in Europe, and it is sometimes these objects that chronicle what the soldiers themselves couldn’t voice.

Recently, Dan Distefano, the son of liberator Salvatore Distefano, contacted the Museum’s Collections & Exhibitions department about some World War II artifacts his father had taken home with him in 1945. Dan had no idea these artifacts existed until 2018. As Dan explains, “In 1952, Salvatore Distefano and his bride, Frances Roberto, purchased furniture for their new life together. Part of that purchase was a smart, cherry wood suite of bedroom furniture. Oddly, the double dresser had room to hide valuables under the second layer of drawers. It was there my dad hid his cache of WWII artifacts and memories from his wife, his children and himself.”

Sgt. Salvatore Distefano grew up in West New York, NJ. Born in 1923, he enlisted and served in the 120th Evac Unit, which liberated Buchenwald concentration camp. [Editor’s note: Buchenwald was liberated on April 11, 1945.] After raising four children, working for forty years as an engineer, and living a lovely family life in North Jersey, Salvatore died peacefully in 2014 at the age of 90. His wife went into assisted living in 2018. When her son Dan was tasked with finding some documents of hers, she suggested he check the “secret compartment” of the dresser.

This is how Dan came across what he refers to as “my dad’s time capsule, hidden there from 1952-2018, ready to tell the story he could not. Even my mom was not aware of the items except the book published by his unit.”

Dan further notes, “Of these items the detailed, working map of Buchenwald was the most touching, as on it he had written in pen: ‘Distefano-Liberator.’ It spoke of how he saw his role in history and I’m sure what he saw reflected in the faces of the people he treated in and out of surgery.”

Other objects in this hidden compartment include a book called Buchenwald and Beyond created by the 120th Evac Unit troops to document their experiences, and a military issue of Time Magazine with an article about important people touring Buchenwald, most likely at the same time that Salvatore was there.

After finding the hidden items, Dan brought his mother home for a time. He writes, “When she arrived, the first thing she said was, ‘I want to see the map.’ I retrieved it and we all stood over it in our family kitchen taking pictures and poring over the extensive detail in it. It was large, hand-colored, numbered and lettered in the best manner with obvious additions and edits made as the camp changed.”

It was also in remarkable condition, probably because Sal had kept it hidden and untouched for so many years.

Though the family was inspired by their father’s artifacts, it wasn’t until they went missing that the family realized how important it is to find a safe place for objects like these. Dan’s mother had hidden them away again, but not in the “secret compartment” – and she no longer remembered where they were. Dan explains, “Easy enough to search a house from top to bottom looking for something familiar, unless of course, a burst pipe intervenes and causes $60,000 of water damage. Sigh! But I was confident that the items had not been destroyed as they didn’t show up during disaster mitigation and demo. Three months of searching had yielded nothing and to say that I was nervous they were gone forever is an understatement. Twenty-four hours before the start of construction I finally found them in a seemingly empty garbage bag on the floor in one of the bedrooms.”

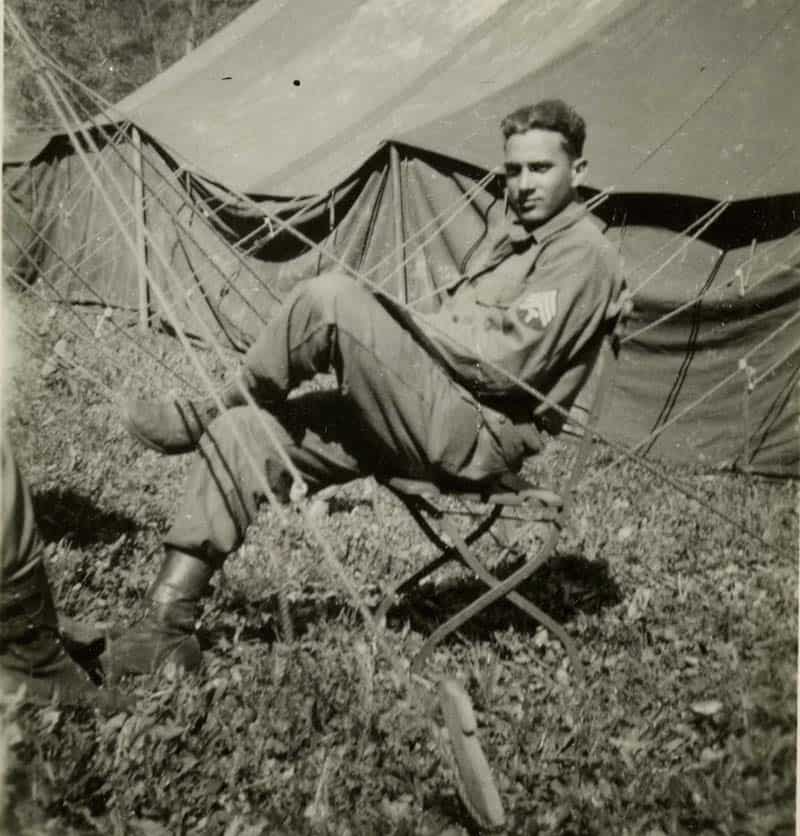

In March of 2018, realizing the importance of the World War II objects, Dan set about making scans of both the book and the map so that he and his siblings each had copies. The family agreed that these items needed to be donated to a museum to be properly preserved and shared with others. Later, Dan recovered more pictures that were taken in camp during his tour of duty mixed in with family photos. As he tells it, the photos “illuminate what it was like to live the life of a soldier on the path to becoming a liberator.”

The Distefano family decided to donate what Dan calls his family’s legacy to the Museum to honor the service and the role that their father, Sgt. Salvatore Distefano, played in history. Sal was not even 23 at the time Buchenwald was liberated, and we can only imagine how he processed the horrors he witnessed while serving with the 120th Evac Unit. But thanks to the discovery of his hidden artifacts, the historical record of the Holocaust is bolstered for researchers and educators of the future.