As our country and the world face heightened racism, antisemitism, xenophobia, and prejudiced hate speech, each of our individual acts of resistance matter. Arthur Szyk, a Polish-Jewish artist who fled Europe in 1937 and settled in New York in 1940, understood the power of speaking out. He used his artistic talent to fight for human rights around the world.

On a 1934 visit to the U.S., as the National Socialist regime tightened its grip on power, Szyk said, “… an artist, especially a Jewish artist, cannot be neutral in these times. He cannot escape to still lifes, abstractions, and experiments. Art that is purely cerebral is dead. Our life is involved in a terrible tragedy, and I am resolved to serve my people with all my art, with all my talent, with all my knowledge.”

Szyk thus made his art a catalyst for change in social justice movements. During the war, he resisted the Nazis and raised awareness about the persecution of Jews through his work, which ranged from caricatures of Hitler and other Axis leaders to drawings of anti-Jewish oppression abroad. In an effort to shift the public opinion of Americans, Szyk often incorporated American symbols and details into his work.

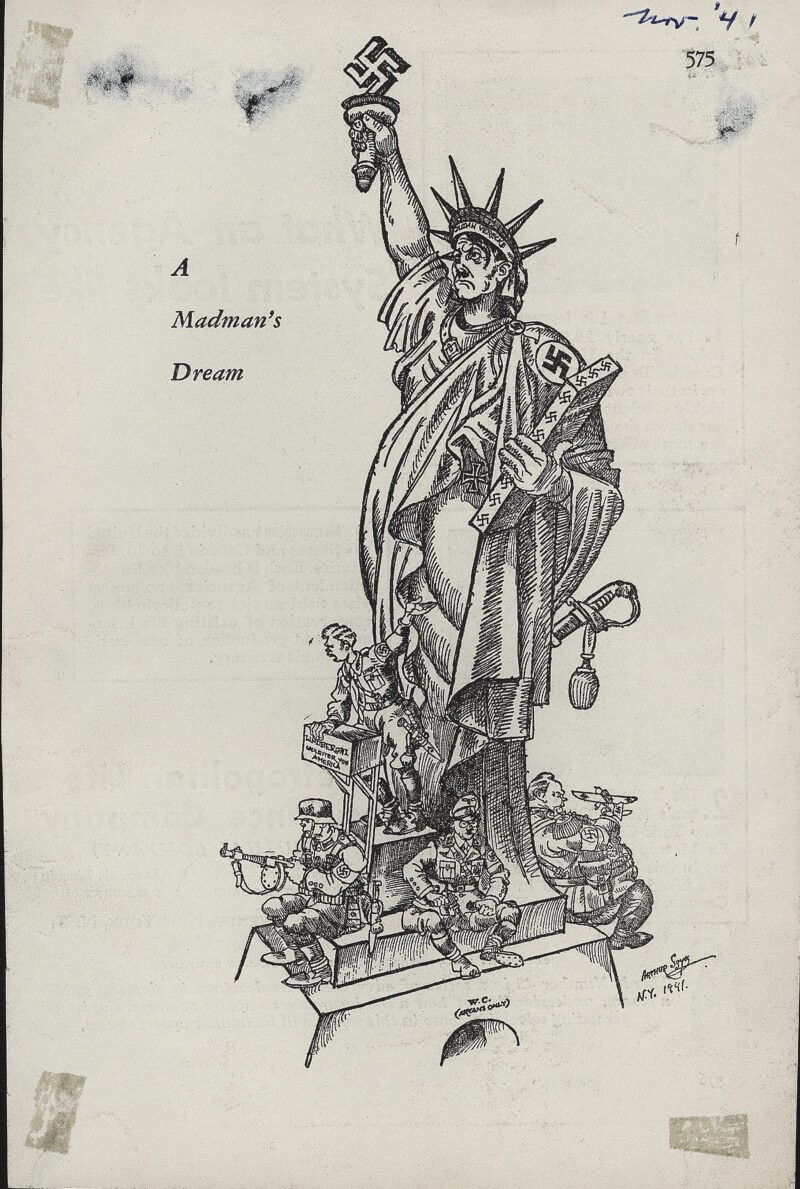

For example, in a political cartoon titled “A Madman’s Dream” from November 1941, Syzk drew the Statue of Liberty overcome by the Nazis. The cartoon, now in the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust’s Collection, was a tear sheet in “The American Mercury” magazine. Szyk replaced Lady Liberty’s hopeful expression with a frowning face resembling Hitler and a swastika instead of a flame in her torch. To punctuate his point, Szyk drew a swastika on her cape and likely a copy of Mein Kampf in her other hand. Three Nazi figures, seemingly Himmler in the center, sit on the statue base, and another individual is drawn preaching atop a “soapbox.” At the bottom is an archway with text over it reading, “W.C. (Aryans only).” At the time of this cartoon, the U.S. had not officially entered the war. By showing the Statue of Liberty, a dominant symbol of American freedom and inclusion, emblazoned with Nazi symbolism, Szyk urged Americans to enter the war and fight Nazi oppression. His political cartoon may be interpreted both as a warning sign of Nazi domination and as a statement on underlying prejudice already present in the U.S.

Szyk also illustrated the “Four Freedoms” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt spoke of in his 1941 State of the Union address: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. The same medieval knight, decorated with the stars and stripes, appears in all four images speaking, praying, feasting, and fighting. In the Museum’s Collection of Szyk’s work, we have a set of four stamps from 1944 printed by the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe with Szyk’s “Four Freedoms” drawings. The Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe was founded in 1943 by Hillel Kook, a member of the IZL Revisionist Movement who worked under the pseudonym Peter Bergson. That Szyk’s “Four Freedoms” drawings representing democracy were used to advocate for the rescue of European Jews reveals he, and Bergson, wanted Americans to view the persecution of Jews abroad as an existential threat to democracy everywhere. Furthermore, by using drawings inspired by Roosevelt’s own 1941 speech, the stamps pressured the government to take immediate action to save European Jewry.

After the war, Szyk turned to civil rights issues at home in the United States, including the anti-lynching movement. Black American communities were terrorized by the threat of lynching throughout the early 20th century. Upon returning from Europe, African American World War II veterans faced particularly heightened violence. Young Black men were often attacked for wearing their U.S. Army uniforms or even mentioning their veteran status. In 1948, only three years before he died, Szyk drew an African American war veteran bound and chained by two hooded Ku Klux Klan members. Below this scene, he wrote a condemnation of anti-Black lynching as a national disaster. Because the pencil drawing was never published, its specific purpose remains unknown. However, this drawing suggests that, like many American Jews in the postwar era, Szyk recognized a direct connection between the Holocaust and the violent oppression of African Americans in the United States.

What I find most interesting about Szyk’s art is how present it was in everyday American life; I can imagine a New Yorker mailing a postcard with Szyk’s drawing on the stamp or flipping through a magazine to see a tear sheet advocating for the Jewish people. His work was extremely popular in the 1930s and 1940s, appearing both in exhibitions and in many magazines and newspapers such as Collier’s, Esquire, Life, Time, and The New York Times. Szyk’s pointed messages through art made their way into American homes on coffee tables and shared moments around the dining room. Americans absorbed Szyk’s artwork all around them, and in the process, his cries for democracy and freedom.

Szyk’s artwork before, during, and after the Holocaust is a remarkable form of resistance and perfectly exemplifies the slogan of the Bergson Group (a group Szyk supported): “action – not pity.” Please explore the slideshow below for more of Szyk’s artwork in the Museum’s Collection, including the program he illustrated for the 1943 “We Will Never Die” pageant.