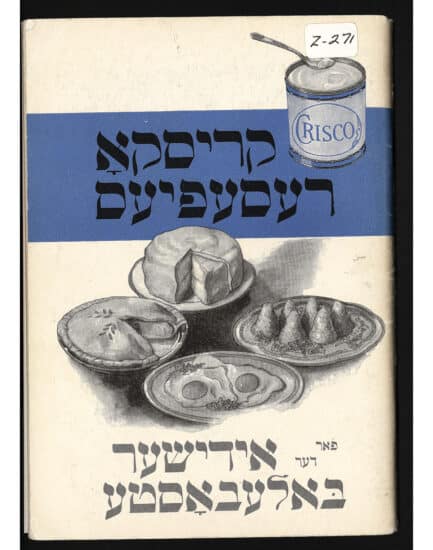

Crisco Recipes for the Jewish Housewife, an English and Yiddish language cookbook, captures a unique and significant moment in Jewish culinary history. In 1935, when this book was published, the newly engineered ingredient Crisco was becoming increasingly popular across the United States, not least of which with Jews, who turned to Crisco as a means of cooking certain modern American recipes while keeping kosher. This dual-language recipe book epitomizes the meeting of tradition and modernity in the New World, where cultures clashed to form delightful new culinary traditions.

Gift of Iris Lasky. 1999.A.49.

Four Thousand Years in the Making

At the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, millions of European Jews were immigrating to the United States to escape various social ills, from poverty to pogroms. Many of these immigrants sought to assimilate to American culture while also maintaining the essence of their Jewish heritage. However, not all American dishes were achievable using the staple ingredients of kosher cooking. That is, until the invention of Crisco.

Invented by Proctor & Gamble in the early 1900s, Crisco was a new fat derived from crystallized cottonseed oil. Since it exclusively used vegetable products, Crisco qualified as “parve,” a food without any animal products that Jews can use in either dairy-based milkhik (halavi) dishes or meat-based fleishik (basari) dishes.

As a parve cooking fat, Crisco solved a dilemma that many Jewish cooks faced in adapting common 20th century American dishes to Kosher law. For example, flaky pie crusts were a common component in American cooking in the early 20th century. But there were no parve fats that enabled Jewish cooks to create parve pie crusts which could then be served alongside both meat and dairy meals.

Gift of Procter & Gamble. 517.88.

When Crisco arrived, the situation changed. Flaky crust requires a solid fat. Dough must enter the oven with pebbly chunks of cold fat; as the glutens solidify, the solid fat evaporates, slowly creating the air pockets that account for the dough’s flakiness. While butter and schmaltz, a rendered chicken fat, were formerly the only options available to Jews, neither of them parve, there was a new fat in town. At last, Jewish cooks could incorporate Crisco into dough as pebbly chunks and achieve a parve flaky crust that they could serve with milkhik or fleishik meals.

Crisco’s uses extended beyond pastry making. Earlier Kosher cooks had often employed butter and schmaltz when greasing their pans for milkhik meals and fleishik meals respectively. Ashkenazi Jews who lived in Europe or who had recently immigrated from Europe had little access to or knowledge of parve fats such as olive oil that would have been more common in some Sephardic Jewish communities. However, the arrival of Crisco provided these cooks with an alternative to butter and schmaltz that many soon came to prefer. Now a cook could grease their pans or do their frying with something parve.

All that remained was for Proctor & Gamble to convince the Jewish public of Crisco’s unique properties. The company started by marketing it as a “cleaner” fat, a message pushed not only with Jews but with the entire American public. It soon obtained testimonials from rabbis. Proctor & Gamble attributes to Rabbi Moses S. Margolies the famous quote that “the Hebrew Race had been waiting 4,000 years for Crisco.”

In the 1930s, Proctor & Gamble hired advertiser Joseph Jacobs to direct their marketing campaign for Jewish communities. Jacobs is one of the brains behind the cookbook Crisco Recipes for the Jewish Housewife. Its alternating English and Yiddish passages allude to the changing demographics of the public that he sought to address: families composed of Old World elders and New World youths, many concerned with preserving tradition but also yearning to fit in.

Sure enough, Crisco quickly became a fixture in the life of American Jews. No food better encapsulates the shift in Jewish cooking oils than latkes. It remains de rigueur to cook latkes in Crisco to this day. One recipe for buckwheat latkes in the book shows this marriage between tradition and innovation.

Buckwheat Latkes

Ingredients:

- 1 cake yeast

- ½ cup lukewarm water or milk

- 2 tablespoons lukewarm water

- 1 cup white flour

- 1 teaspoon sugar 2 raw potatoes (ground fine)

- 1 teaspoon salt

- 2 cups buckwheat flour

- 2 tablespoons Crisco

- ¼ cup lukewarm water or milk

Directions:

Dissolve the year in the 2 tablespoons lukewarm water. Add to the sugar, salt, and Crisco which have been mixed with the ½ cup of lukewarm water or milk. Stir in the 1 cup white flour and allow to rise for ½ hour in a warm place. Then add the finely grated potatoes and the ¼ cup water or milk and stir in the buckwheat flour. Allow to rise for 2 hours.

Place heaping tablespoons of this mixture on a hot, well-Criscoed pan over a direct fire and after turning once, bake in hot oven (400° F.) for 20 to 25 minutes.

Makes 18 to 24.

A recipe for Strudel Dough in this cookbook shows the incorporation of Crisco into traditional Jewish dishes.

Strudel Dough

Ingredients:

- 1 egg yolk

- ½ cup hot water

- ½ teaspoon salt

- 2 tablespoons melted Crisco

- 2 to 2½ cups flour

Directions:

Beat the egg yolks in a bowl. Add the salt, hot water, and melted Crisco, beating up quite well. Mix in the flour gradually, but work fast enough so that the dough does not get cold. Knead well or beat on board until it is velvety and smooth. Brush with a little warm melted Crisco and cover. Allow to stand in a warm spot for 20 to 30 minutes.

Flour an old, clean tablecloth. Place one half of the dough on this. Roll out quickly to about ½ inch thickness. Then using the back of the hands, draw the dough out carefully from the center outward. Keep moving the hands and the stretched dough until a paper-thin sheet is obtained. Sprinkle liberally with melted Crisco.

Have filling prepared and ready to use.

Crisco might not be the health food that Americans once imagined it to be. However, it still tells the story of a jolting cultural shift that would leave an indelible mark on Jewish American cuisine, giving kosher American Jews a way to bridge their religious beliefs and their national identities.