By Olivia Maccioni, Outreach & Visitor Experience Coordinator at the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust

On a dark winter evening in February 1885, police officers descended on Seeger’s Restaurant, a small bar located in central Berlin. Although close to government offices and cultural institutions, the pub was surrounded by a quiet residential neighborhood, dotted with small stores and businesses. The simple interior was typical of many Berlin taverns: the front door faced the street and opened into a small room with an oak bar, tables, and chairs; from there a doorway led into a second, larger room, where more tables, chairs, and a sofa were arranged. . . . The men in the bar–there were no women–came from all walks of life and included tradesmen, merchants, and professionals. What drew them to Seeger’s Restaurant was the opportunity to meet men who preferred men, for love or sociability, and to do so in a safe environment. (Chapter 2, “Policing Homosexuality in Berlin,” Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity)

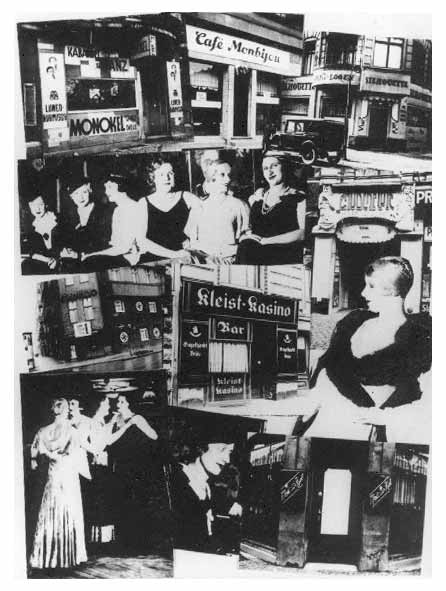

By the turn of the nineteenth-century, Weimar Republic Berlin was dotted with street-side booths circulating gay activist literature, nights lit with banquets hosting drag balls, and in 1919, saw the establishment of German-Jewish physician Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexuality. Hirschfeld’s Institute in central Berlin was the first of its kind – it housed a library on sexuality, provided educational services, and gave medical consultations that included some of the first sexual reassignment surgeries for trans-people.

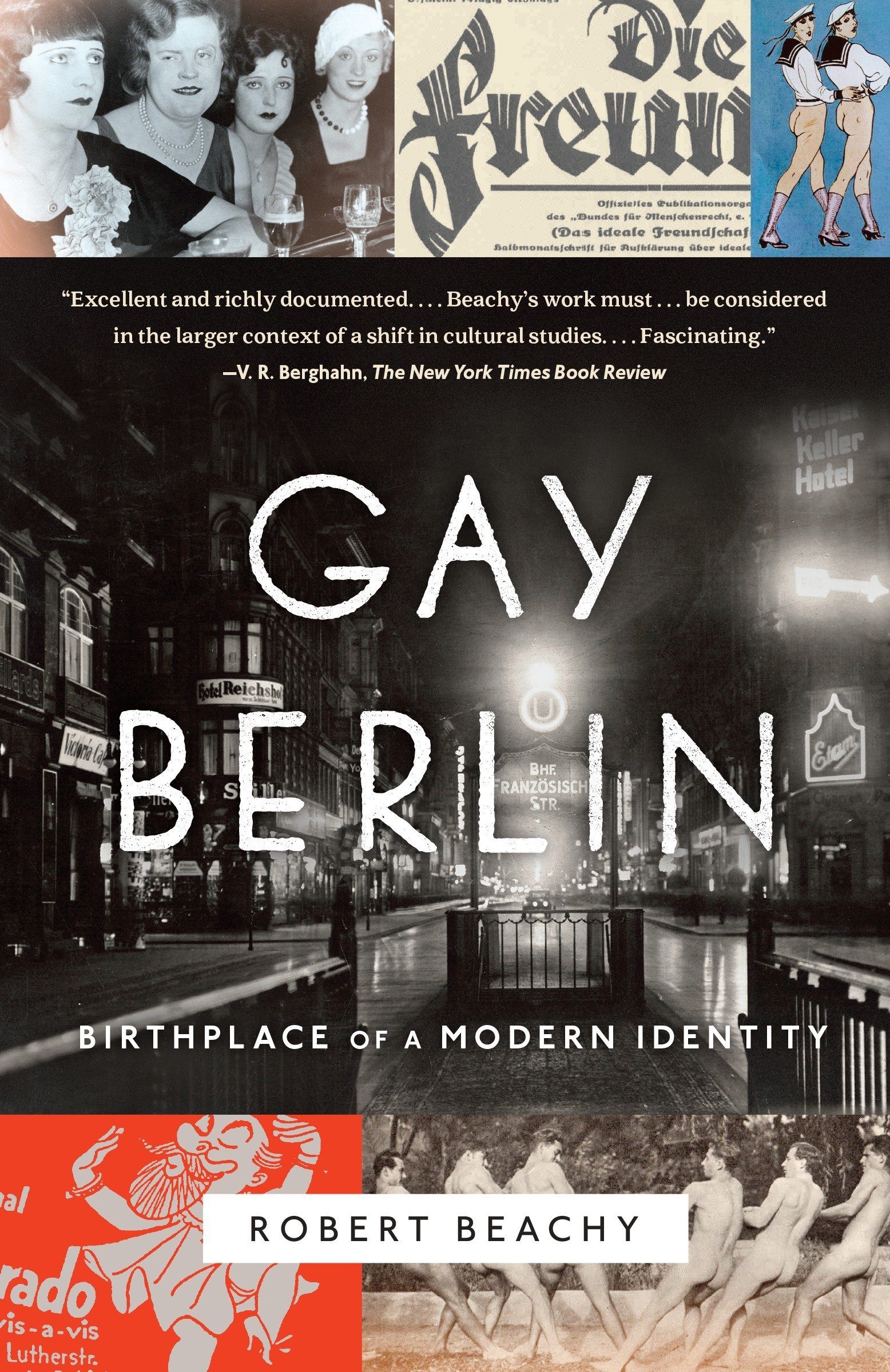

In other words, Weimar Germany witnessed arguably the first international gay rights movement with Berlin at its center. According to Professor Robert Beachy, author of Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity, liberal policing, a relatively free press, and a burgeoning art and culture scene attributed to the potential possibilities of openly gay communities in early-twentieth century Berlin.

Robert Jan Van Pelt, Chief Curator of Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., also speaks of the importance of showcasing this complex milieu in the Museum of Jewish Heritage’s newest exhibition. Van Pelt notes, “It is important in our exhibition to provide a fair representation on the aspects of the past [that] we present. And if one only shows the Weimar Republic as a time of political shambles, it would not be a fair picture: Germany in the 1920s was also a culturally vibrant place, and we at least wanted to touch on that.”

Yet, less than a decade after the Weimar began, many individuals involved in this early gay liberation movement, including Magnus Hirschfeld –born a German-Jew– began to feel the pressures of the rise of the Nazi party. As indicated by the passage from the book above, homophobia always remained a constant threat to progress for civil rights activists in Weimar Germany and quickly worsened as the Nazis began to take power.

Hirschfeld began a World Tour to share his ideas outside of Germany in 1930, stopping in New York City for six weeks in the fall of that year. However, due to continued waves of anti-Semitism in Germany, he settled in France at the end of his trip and never returned home. On May 6, 1933, less than four months after Hitler was appointed chancellor, and a little over a decade after its foundation, Hirschfeld’s Institute was sacked and its books burned in public book-burnings.

Only a few decades after Hirschfeld’s visit to New York and the demise of his Institute, in the early morning hours of Saturday, June 28, 1969, nine policemen entered the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, Lower Manhattan. The scene at Stonewall was reminiscent of conflicts that occurred between the LGBT community and police in Berlin decades earlier. The Stonewall Inn, like Berlin’s Seeger’s Restaurant, was once a place where the LGBT community could feel safe.

Pride is a time to come together and celebrate the strides of gay rights activism and liberation. This year, the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising also begs us to reflect on the histories and struggles that have come before us, remember those who have passed, and take note for the future.

The Museum’s newest exhibition, Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., an exhibition that brings together more than 700 original objects and 400 photographs from over 20 institutions and museums around the world, includes artwork and artifacts of the Weimar Berlin LGBT community.

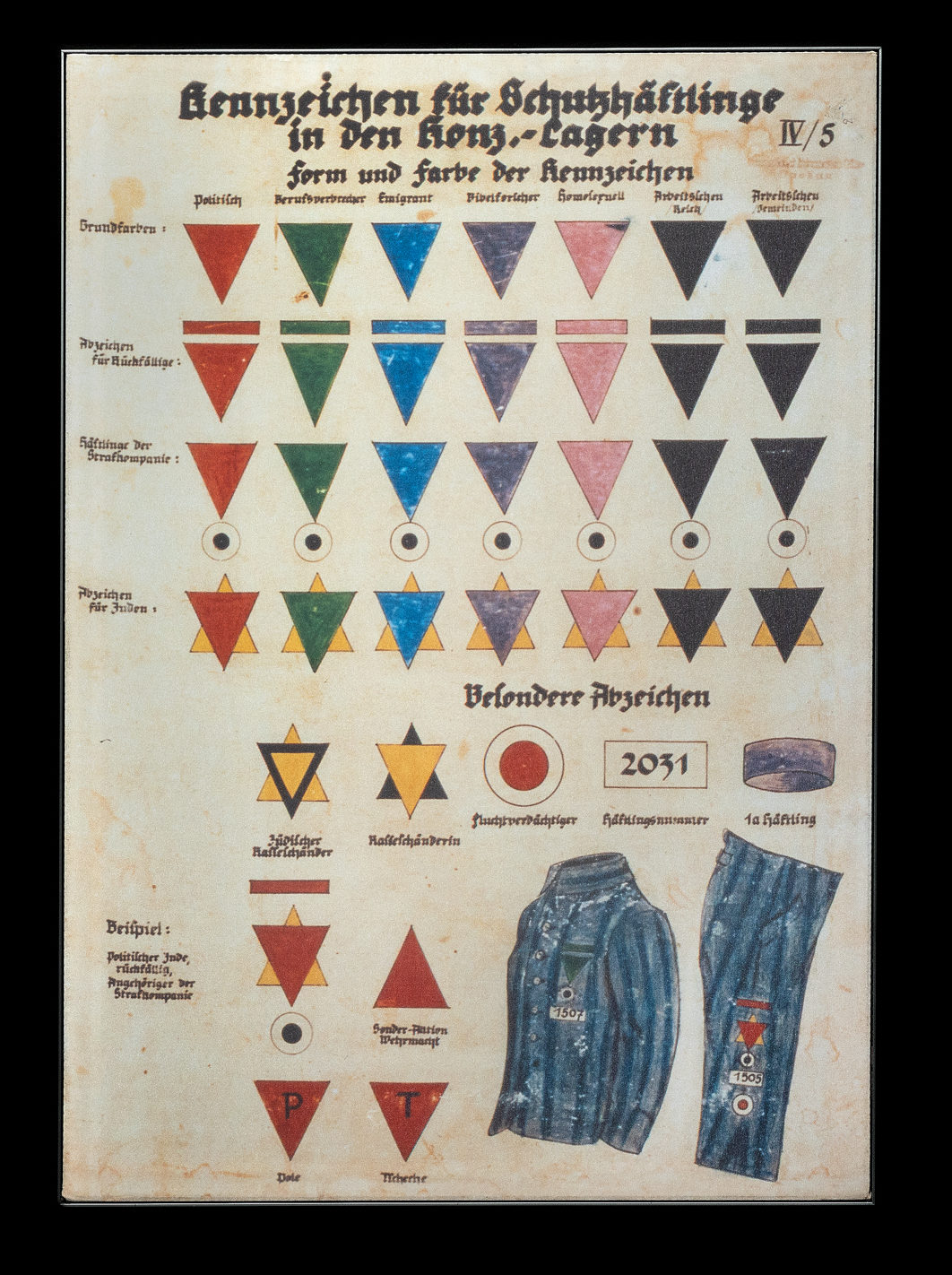

At the end of the exhibition’s first floor is the story of The Pink Triangle – a symbol used to demarcate individuals in concentration camps who were imprisoned for their homosexuality. Curator Van Pelt notes that this section is specifically included “because it is part of the historical record. In the concentration camps the homosexuals were identified as a special group of prisoners, marked as such, and treated with special severity.”

In the mid-1930s the Nazis began to target male homosexuals, as they challenged their ideals of masculinity and fatherhood. One hundred thousand men were arrested under Paragraph 175 of the penal code, which criminalized male homosexual sex; 50,000 were convicted, and more than 10,000 ended up in concentration camps. Marked by a pink triangle, those imprisoned under Paragraph 175 were the targets of particular abuse.

Besides illustrations that showcase the symbol’s use, this section also contains a silkscreen copy of artist Richard Grune’s lithograph, Passion of the 20th Century. Grune was formally trained at the Bauhaus school in Germany under teachers including Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. He was a key member of the Kinder Republik, a free children’s republic organized in 1927 that taught children the importance of democratic participation, tolerance, and respect for fellow human beings. Grune survived the Holocaust after imprisonment for almost eight years on a “denunciation” of homosexuality. After the war, he continued his art practice and created lithographs that detail his experience during the war. However, when exhibited, they were often ridiculed and destroyed. As Curator Robert Jan Van Pelt notes, his story “allows us to give a name to the experience of male homosexuals in Nazi Germany, and also show that . . . the massive violation of human rights that the camps represented emerged from prejudices that did not disappear in 1945.”

The Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust’s newest exhibition, Auschwitz. Not long ago. Not far away., is a testament to the continued forces of hate in our world today and an examination of the destructive power of hate in the past. Through reflecting on humanity’s darkest moments and sharing the stories of individuals who fought for acceptance, freedom, and self-expression, we can begin to truly appreciate the fragility and sacredness of our present and future.

On June 13, 2019 the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust hosted a conversation between authors Robert Beachy and Eric Marcus about Beachy’s book, Gay Berlin: Birthplace of a Modern Identity. Gay Berlin is not only an incredible resource and reframing of early gay history and gay rights activism, but also, a warning for our times of the historic power of hate to destroy the power of love.

On Wednesday, June 26, at 7PM, the Museum will be hosting another public program in conjunction with the Stonewall 50 Consortium co-presented by The Generations Project. There will be a film screening of Dear Fredy; a film that follows the story of Fredy Hirsch, an openly gay German Jewish athlete living in Nazi Germany in the 1930’s. The film will be followed by a post-screening discussion with Michael Simonson of the Leo Baeck Institute.

Watch the conversation between Robert Beachy and Eric Marcus: