Toma Ion and Marita Toma Radulescu were nomadic Kalderash Rom living in a region between the Danube River and the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. Toma worked as a coppersmith, and Marita as a fortune-teller. Their grandson, Iulian, wrote in 1999 that, “my grandmother, like all the women, was taking care of the tent and children but also she was a fortune teller… No fortune teller could ever predict what was going to happen to them. It was the summer of 1942 when the authorities of Romania, under the Hitlerist regime, decided that Roma people are not useful and had to be terminated.”

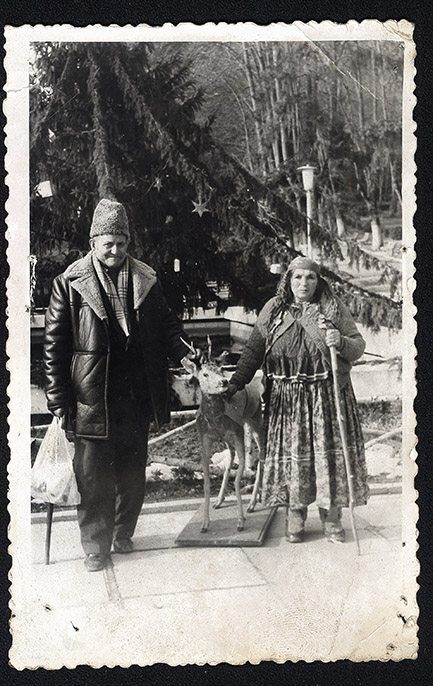

Between June 1 and August 9, 1942, Romanian police told the Radulescus and other nomadic Rom that they were to be resettled on short notice to an unspecified location. Toma and Marita had to quickly decide which items to bring with them. Both of the Radulescus brought hand-made clothing, such as Marita’s floral, red blouse and floral head scarf pictured below.

Toma and Marita were able to bring pieces of their prewar life with them to the camp they were sent to in Transnistria. Besides their clothing, they both chose belongings related to their respective professions. Toma, a coppersmith, brought a number of tools with him, including tongs (the Romani term is clestiuri) for holding copper in the fire while hammering, a metal hammer (ciocan), a soldering iron (lectomo), wood mallet (copal), and more. Marita selected a wool pocketbook (tisa) which tied at the waist and primarily stored sea-shells used for fortune-telling.

Among the other possessions the couple travelled with were a copper tea-kettle (samovari), sieve (sita), and kerosene or oil lamp (festila). Perhaps most important, however, were the gold coins Toma successfully smuggled. Before the Romanian police searched the Roma for gold, Toma swallowed as many gold coins as he could. The Radulescu’s retention of gold coins contributed tremendously to their survival. At the Crivoi camp in the Golta region, Toma used the gold coins to bribe Romanian guards to procure food and various necessities.

After nearly two years in the camp, Roma learned that the Germans were losing the war, and their Romanian guards started to disappear. Toma and Marita escaped from the camp in the spring or summer of 1944, and took their tools and remaining pieces of clothing back with them across the Dniester River to Romania. Many Roma fled Transnistria that summer, especially following the dissolution of the Antonescu government on August 23, 1944, and Romania’s declaration of war against Germany two days later. Of the 25,000 Roma deported to Transnistria, only about 6,000 survived and returned to Romania like the Radulescus. Many others died from disease, starvation, and brutal treatment.

Toma and Marita remained in Romania for the rest of their lives. Their son prospered in the construction industry. Their grandson, Iulian, escaped Communist Romania in 1987 by swimming three hours in the Danube River to Yugoslavia. He eventually settled in the United States. Iulian fought for Romani rights in the U.S., and members of the Radulescu family were among those who represented Roma in negotiations with German authorities for reparations in the nineties.

It was Iulian who brought his grandparent’s belongings to New York and the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust. On a trip to Romania in 1999, Iulian asked Toma, 84 at the time, for these artifacts. According to Iulian, Toma took out Marita’s clothing, wept while he remembered their years together, and handed them over to Iulian. But when Iulian asked for the tools as well, he asked, “How can I give my tools away?” Iulian explained that this was an opportunity to help the Roma people by educating the world about how they were deported, “something they don’t know and don’t care about.” His grandfather Toma then said, “I may never see you again. Take them.”

Every one of us who learns about the Radulescu’s story contributes to Iulian and Toma’s wish that their family’s surviving possessions may teach the world about the persecution of Roma people under the Nazi regime. Scroll through the slideshow below for images of more of the Radulescu’s belongings now in the Museum’s collection.

#StoriesSurvive