By Olivia Maccioni, Clare Manias, and Treva Walsh

I drew the pictures in this book at a displaced persons’ camp in Deggendorf, Bavaria. I had come there in July of 1945, ten weeks after having been liberated from three and a half years of imprisonment in three Nazi concentration camps. The drawings took about two months from the day a Deggendorf bookbinder had sewn together a book of blank pages for me. With all the impressions of the detention years still in my mind, this was a perfect opportunity to record them in detail. (Alfred Kantor, “Introduction,” The Book of Alfred Kantor)

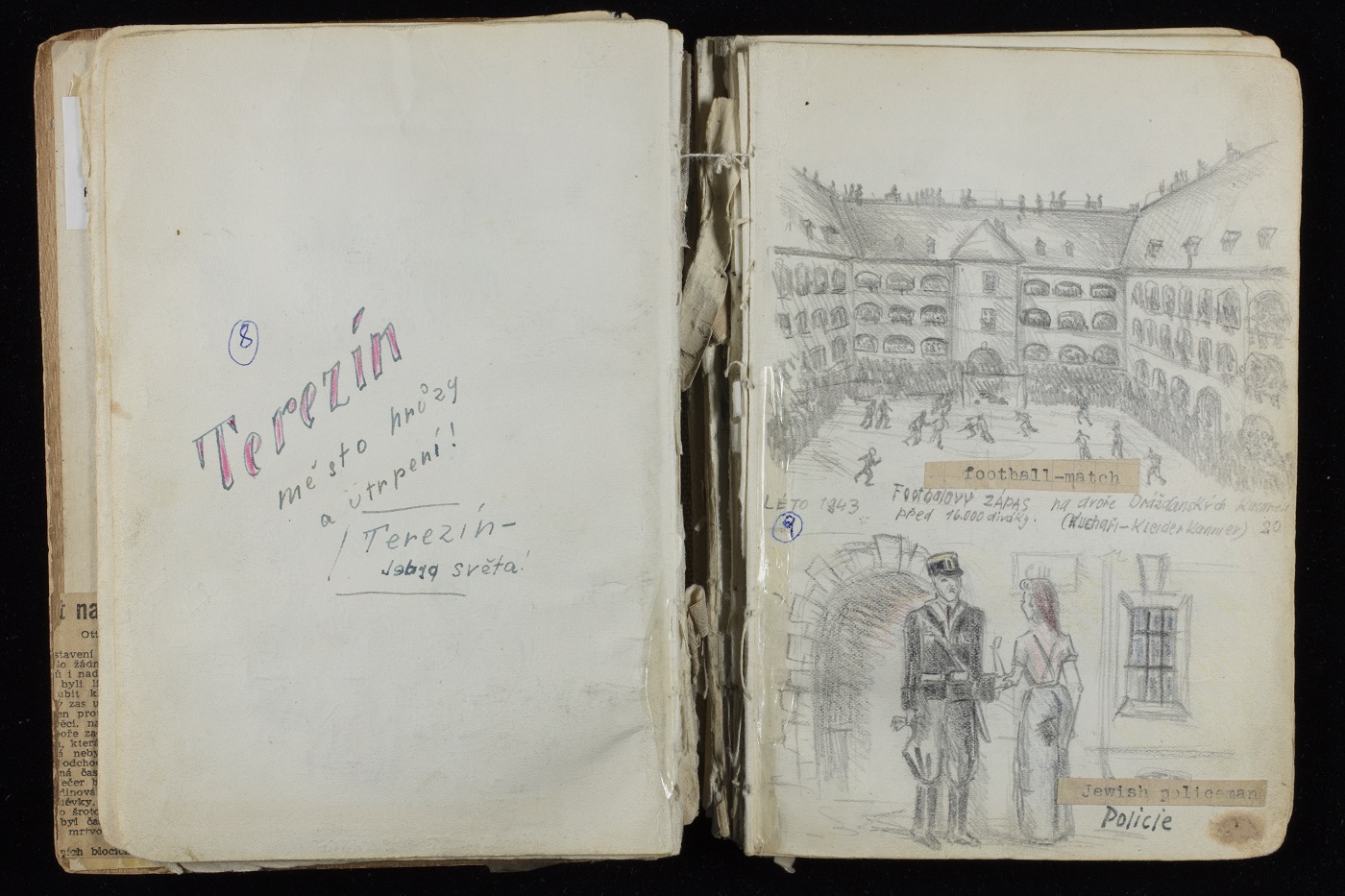

With the help of rare book Conservator and bookbinder Clare Manias, the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust recently completed a full repair and conservation of the 1945 sketchbook and portfolio of Holocaust survivor and artist Alfred Kantor. Representing his experiences in Terezín, Auschwitz, and Schwartzheide, these uniquely personal artifacts will now be preserved for research, exhibition, and education for years to come.

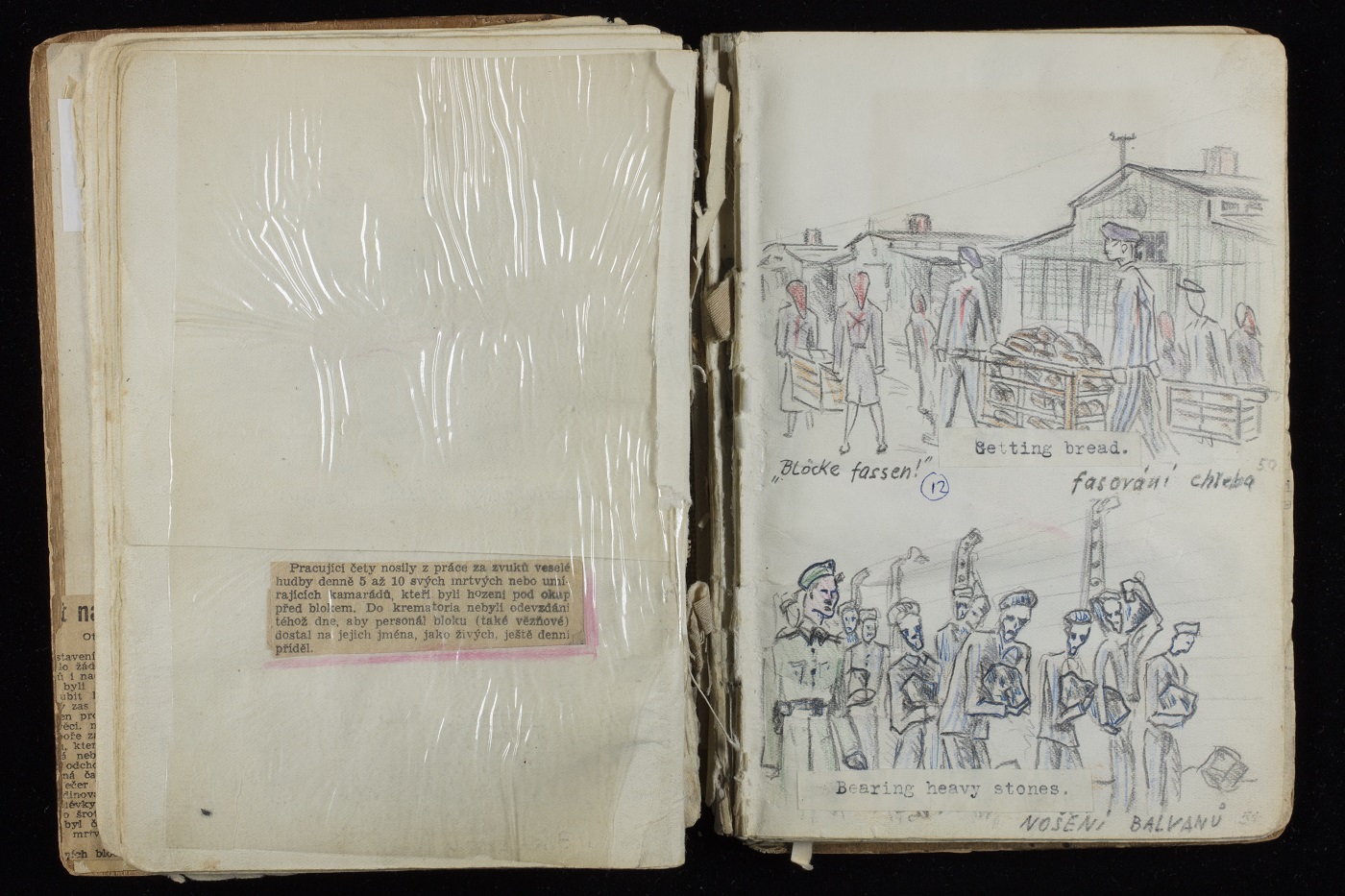

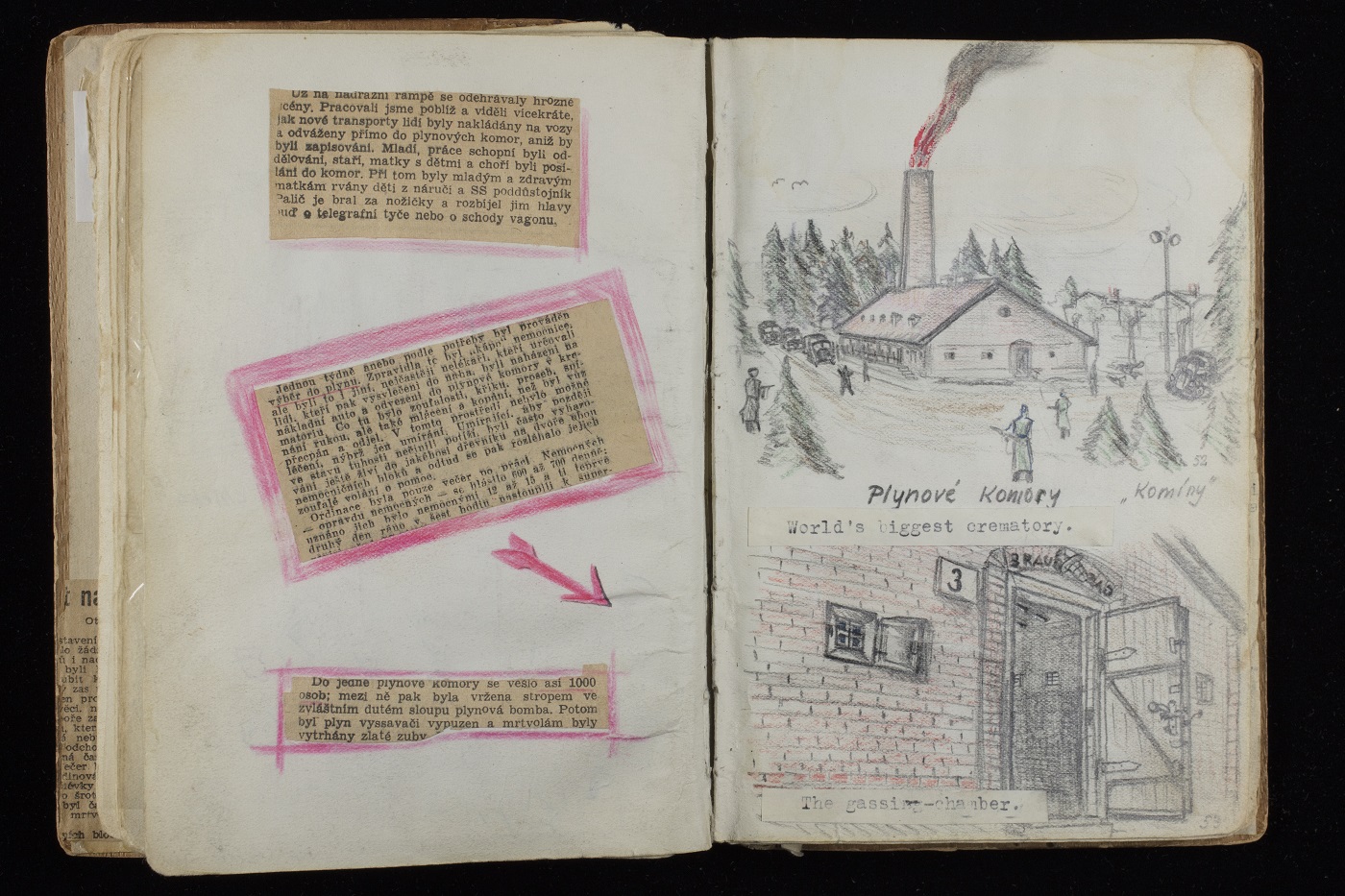

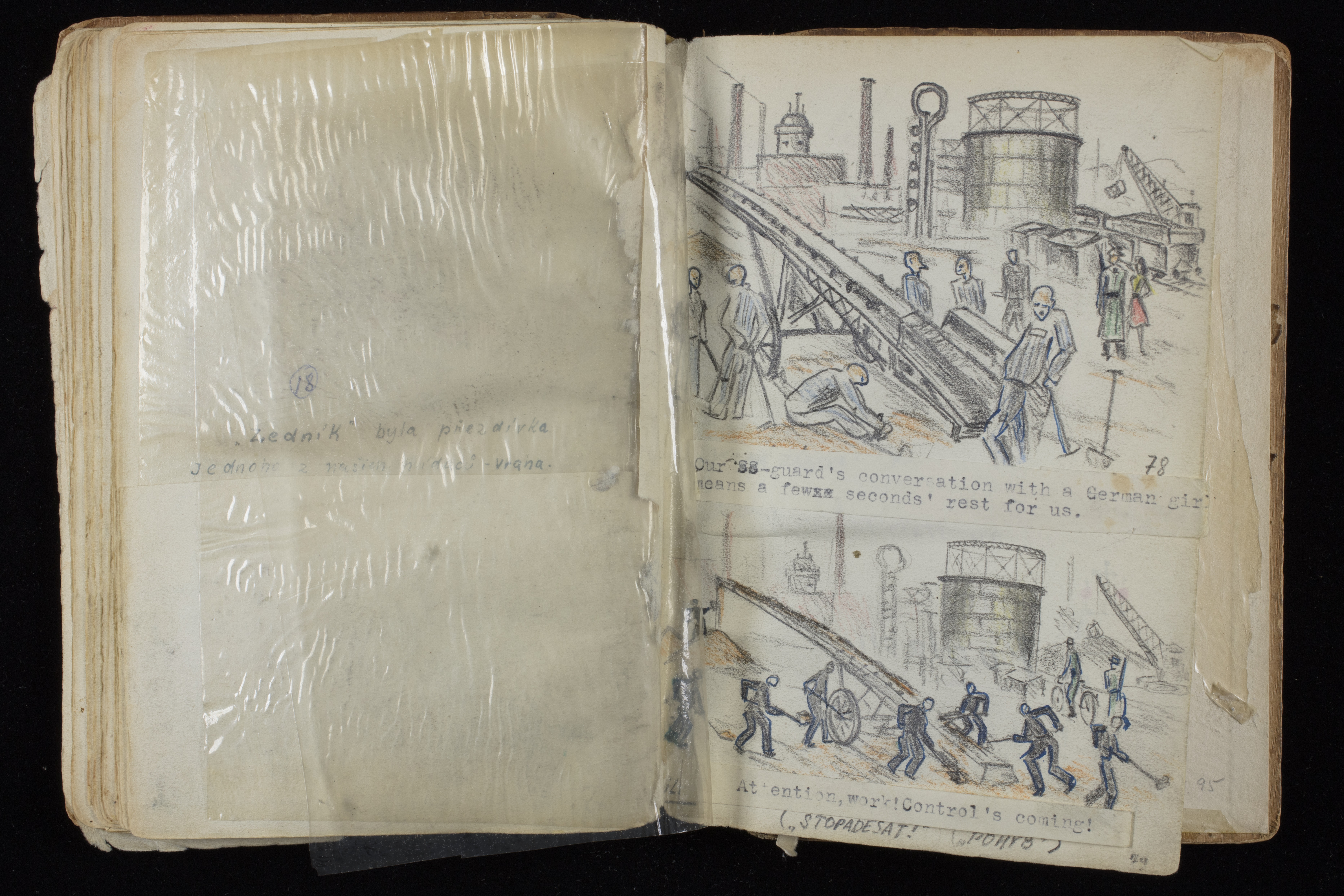

The sketchbook and portfolio feature intimate drawings and sketches laid side by side with postcards to family, a deportation order, a yellow star, and a uniform number patch. A stark visual testament to the horrors of the Holocaust and WWII, the books also live as a man’s personal journal during the darkest years of his life. For Conservator Clare Manias, this meant that the process of repairing the books was a double-edged sword — she had to emotionally distance herself in order to think of best conservation practices, while also keeping the integrity of a man’s diary steeped in time and memory.

Of the experience, Manias writes,

I wondered why looking at these images for 7 hours a day didn’t depress me. I think it’s partly because I was thinking about the paper, tape, adhesive stains, and bindings. It was the reflection of the humanness of Kantor and other prisoners that I found inspiring. Intermingled with horrors, there are images of inventiveness, kindness between prisoners, relationships, and irony that used the power of art to tell a powerful story that left me in awe.

Alfred Kantor was born on November 7, 1923 in Prague, Czechoslovakia. He had always enjoyed drawing and planned to attend the Rotter School of Advertising Art. However, as Nazi Germany began occupying Eastern Europe, barring Jews from universities like the Rotter, Kantor’s path quickly changed. He and his family considered fleeing Czechoslovakia but were forced to stay in Prague due to his father’s quickly declining health. In late 1941, two weeks after his father’s death, Kantor received his deportation notice.

Kantor was among the first Czech Jews deported to Terezín, where he was forced to help build the ghetto. In 1942, he was joined by his mother and a friend from Prague named Eva Glauber. Together, they were able to survive on the extra food procured by Kantor while working in the kitchens and the regular food packages from Kantor’s sister, Mimi, who was saved from deportation because she was married to a non-Jew.

Kantor began drawing scenes of daily life while in Terezín, where he kept a notebook of sketches and drew pictures as souvenirs for other prisoners. In Auschwitz, he managed to find paper and pencil and continued to draw, although he had to destroy the pictures. He later told his son that drawing pictures at Auschwitz of what he saw and lived through allowed him to process the horrors and difficult situations as an observer rather than as a victim. He was allowed to draw while visiting Eva in the infirmary, which was staffed by other prisoners. Surveillance was heightened at Schwarzheide, and while Kantor had to destroy most of his drawings there, a few small pictures survived thanks to a friend who smuggled them out. After liberation by the Soviet Army, Kantor moved to the Displaced Persons camp in Deggendorf, Germany, where the rescued drawings and the images he committed to memory became the basis for the sketchbook.

As a result of this artistic process, the sketchbook and portfolio were put together without carefully planned, long-term conservation in mind. Manias notes that tape—often used instinctually to place objects like this together—ultimately leaves terrible dark stains, embrittles the paper, and then gives out. From a historical point of view, however, she writes,

. . . the tape is now a part of this object’s history, especially if the artist him–or herself–put the tape on the object to repair it. This creates a dilemma because I know that the tape is causing damage, but I can’t simply take it off. I have to consider if the historic aesthetic will be preserved. If the tape is falling off, or falls off while the treatment is progressing, or must come off in order for the treatment to progress, I have to consider that I might have to put it back on.

The spines of both books were–are–covered with layers of tape. What looked like the oldest layer on the sketchbook was darkened in the center, the area where you would hold the book while reading it or showing it to someone else. The oils from Kantor’s and other readers’ hands had made the tape hard and brittle. But those stains and discolorations were from the hands of the artist, the same person depicted in the images, the same person who made the images and lived through the crimes and bitter heartbreaks they depict.

I decided to remove the outer, newer layers–the layers that covered the stains–and consolidate the remaining layers with a reversible acrylic adhesive that would also act as a barrier to further damage from the acidic carrier. Any tape that disintegrated during the treatment was replaced with an archival handmade paper that looks a lot like masking tape when it’s coated with the reversible adhesive. The new “tape” can withstand the rigors of exhibition and handling and keep the remaining masking tape in place and protected while visitors to the museum can see for themselves, and experience the resilience of this human’s spirit.

In 1943, Kantor’s mother was transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. A few weeks later, Eva was also sent to Auschwitz, and Kantor volunteered to go with her. There, he and his mother were assigned to work on the rock gang, carrying heavy stones for miles to pave a road in the camp.

It was these first few months in the camp that reinvigorated Kantor’s desire to draw and eventually share what he was seeing. There were chilling moments, he writes,

. . . that prompted me to find a way to sketch again. Only now I felt obsessed, driven in fact by the overwhelming desire to put down every detail of this unfathomable place. I began to observe everything with an eye towards capturing it on paper: the shapes of the buildings, the insulators on the barbed-wire poles, the battalions of workers at labor sites, the searching for lice, the women carrying soup in heavy barrels, the incredibly eerie feeling of Auschwitz at night with its strange lights and with the glow of flames from the crematorium. (Kantor, “Introduction,” The Book of Alfred Kantor)

It is in these moments, throughout similar notations in his autobiography, that Kantor’s destined life as an artist is heartbreakingly illuminated. He recalls receiving a package of food from his sister Mimi that contained a lemon. He describes Eva’s joy at seeing such a sight with incredible detail—so much so that the image of the memory draws itself in the reader’s mind. At the camp, Kantor was forced to memorize these moments and draw at night, for fear of the danger of drawing—and being caught—in daylight.

Eva eventually became sick with tuberculosis, and Kantor often visited her in the infirmary, where the prisoner in charge allowed him to draw in a small room. Kantor memorized the scenes he drew and tore his papers as soon as he was finished. Of this time he writes,

I realize that taking it upon myself to single-handedly “expose” Auschwitz with my drawings could only have come while still very young and while still capable of being so brazen despite the bleakest of circumstances. I realize now, too, that this mission served a much greater purpose: and that was that my commitment to drawing came out of a deep instinct of self-preservation and undoubtedly helped me to deny the unimaginable horrors of life at that time. By taking on the role of an “observer” I could at least for a few moments detach myself from what was going on in Auschwitz and was therefore better able to hold together threads of sanity. (Kantor, “Introduction,” The Book of Alfred Kantor)

In early 1944, Kantor’s mother and the rest of her transport were sent to the gas chambers, although the SS told the prisoners that the transport was being relocated to a work camp in Upper Silesia called Heydebreck. Six months after Kantor, his mother, and Eva had arrived at Auschwitz, the Allies bombed a large plant in Schwartzheide, Germany, one of the Nazis’ major suppliers of synthetic fuel. Prisoners from Auschwitz were selected to rebuild it, and Kantor was among the one thousand men who were suddenly sent from the camp to Schwartzheide via railroad. He later learned that Eva was gassed ten days after he left.

At Schwartzheide, almost two thirds of the thousand men died under the unbearable workload. On April 18, with the Allies approaching, the prisoners were sent on a death march out of Schwartzheide towards the Czech border. After waiting two weeks in the Czech town of Varnsdorf, they were put into railcars and sent back to Terezín. There, Kantor was given food, shelter, and new clothes by the Czech Red Cross. He returned to Prague, where he was reunited with his sister, Mimi. After some time, he joined a group of former prisoners who were headed to the displaced persons camp in Deggendorf, Germany, where he acquired a blank sketchbook and began recreating the drawings he had been forced to destroy.

After the war, Kantor made his way to the United States and enrolled in art school. Before completing his studies, he was drafted into the U.S. Army. After his discharge, he completed his art degree and married a woman who also survived Terezín, with whom he had two children. In subsequent years, Kantor reworked the material in his sketchbook into a portfolio of full watercolor paintings.

It is an honor to showcase such intimate, yet painstakingly important, artifacts in the Museum’s newest exhibition. Placed next to artifacts of mechanized death and destruction, Alfred Kantor’s drawings remind us of the power of art–personally and historically–in life’s darkest moments, while also standing as a powerful resistance to Nazi ideology of dehumanization and creative destruction. Alfred Kantor’s sketchbook and portfolio are a point of light; strong reminders of the power of individuality, freedom, and personal expression.

The Sketchbook of Alfred Kantor is a gift of Alfred Kantor. The Portfolio of Alfred Kantor is on loan courtesy of the family of Alfred Kantor.