In response to growing numbers of Jewish refugees seeking haven from Nazi persecution, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt convened (but didn’t attend) the Evian Conference in July 1938. Representatives from 32 countries gathered in Evian-les-Bains, France, to discuss the refugee crisis and how their countries might respond. Many expressed sympathies, but only one country agreed to absorb additional refugees: the Dominican Republic. They worked with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) to establish an agricultural settlement in the town of Sosúa. There, Jewish settlers built a community that still exists today.

In cooperation with the Sosúa Jewish Museum, the Museum of Jewish Heritage – A Living Memorial to the Holocaust, presented a bilingual exhibition, in English and Spanish, in 2008 called Sosúa: A Refuge for Jews in the Dominican Republic (Sosúa: Un Refugio de Judíos en la Republica Dominicana). The exhibition explored this slice of history, which we share here as well, to illustrate how residents were selected, how they came to Sosúa, what awaited them there, and the growth and evolution of the Jewish community there.

In cooperation with the Museum, Professor Marion A. Kaplan conducted three years of research in the JDC Archives, which cumulated into the book, Dominican Haven: The Jewish Refugee Settlement in Sosúa, 1940-1945, upon which the exhibition was based.

Leading Up to Sosúa: Historic Context

As Nazi persecution spread throughout Europe, thousands of Jewish refugees tried to get out. The Dominican Republic was one of the only places that would let Jews in. Most government leaders claimed their countries were too crowded to accept refugees. They also cited high unemployment rates as well as isolationist pressures.

Rafael Trujillo, the President of the Dominican Republic, offered Sosúa. Trujillo was an infamous dictator who also provided a home for 750 Jewish refugees in the island nation’s agricultural settlement.

A Complicated Offer

Trujillo’s motivations were complex. As noted by Professor Marion A. Kaplan, “Trujillo needed to generate good publicity after the international outrage caused by the Dominican massacre of Haitians in October 1937, just nine months before the Evian Conference.”

While in Nazi Europe Jews were considered “racially impure” in certain territories and “too foreign” in others, Trujillo hoped that light-skinned European Jews would bring the “skills, energy, prestige, and capital” which he associated with European citizens who were white. Trujillo hoped the Jews’ intermingling with local Dominican women would result in “lightening” the skin tones of the overall population.

Luis Hess, who lived in Sosúa, contextualized these positions, saying: “The person who wanted to help us was not a humanist. But did we have a choice? Hitler, the German racist, persecuted us and wanted to murder us. Trujillo, the Dominican racist saved our lives.” (Kaplan, 27)

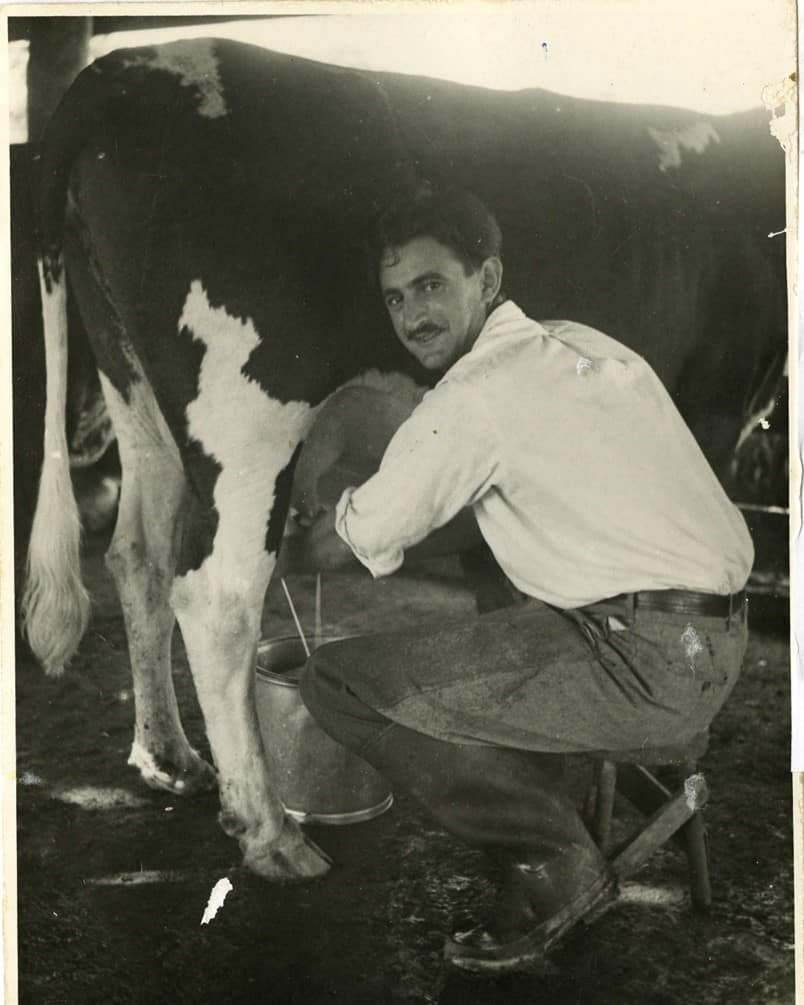

Life in Sosúa

For Hess and his fellow Jewish refugees, Sosúa was a haven with sandy beaches and gorgeous waters. At the same time, with the beauty and tropical climate came challenges of intense heat and mosquitos and rainstorms that made for trouble in the barracks and their plumbing. Refugees had to adapt to a new part of the world.

Additionally, many residents were alone – due to quotas, they could not come to Sosúa with their whole families, and often waited years in the hopes that refugee passes would be granted to extended family members. Sadly, many were never allowed to come to Sosúa, as entry became further restricted as the war progressed.

Jospeh A. Rosen, a member of the American Jewish Joint Distribution who was involved in the Sosúa project, observed of the mental state and collective heartbreak of the refugees as they struggled with missing their families and former lives:

“While nature has endowed collective and individual organisms with remarkable powers of regeneration, it is often much easier to mend a broken body than a broken heart and broken spirit.” Kaplan, 107

Legacy

Despite the struggles, many were able to adjust to life in Sosúa. The community there established a medical office which served anyone on the island, a school for children, businesses, and other partnerships with the local Dominicans. The community came to consider Sosúa their home.

Though many of the original Sosúa settlers left after the war for other locations, including New York, some remained in the Dominican Republic, where they maintained their own businesses and raised families that grew up bilingual and bicultural, cultivating a unique Jewish-Dominican identity.

Though the Jewish presence in Sosúa today is not as large as it was in the past (in 2016 the World Jewish Congress reported that Dominican Republic was home to between 100 and 300 Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jews), its significance remains for the survivors, who expressed immense gratitude toward their Caribbean refuge after so many countries turned them away.

Sosúa: A Refuge for Jews in the Dominican Republic / Sosúa: Un Refugio de Judíos en la República Dominicana

Years later, after generations of the original Sosúa settlers left the Dominican Republic, their descendants understood the emotional significance of what the island meant to the original refugees.

As Kaplan writes in her book, “In a letter discussing plans for a 50th reunion gathering in Sosúa, a child of settlers found a stack of rejection letters that her father had received ‘from a variety of countries to which he applied for immigration…

“You can well imagine, after all these refusals how welcoming the acceptance into the Dominican Republic must have been to my parents. Had Sosúa not happened — who knows about our destiny.”” Chapter 7, Page 173

This history was chronicled in the Museum exhibition, Sosúa: A Refuge for Jews in the Dominican Republic (Sosúa: Un Refugio de Judíos en la República Dominicana), on view from February 17, 2008 to August 10, 2008. The exhibition highlighted Jewish life in the Caribbean and Latin America as well as the legacy of the Dominican Republic in providing a shelter for Jewish refugees during the Holocaust.

The story of Sosúa stands as a reminder of the struggles and challenges Jewish refugees faced in finding safe harbor when the rest of the world shut its doors on them, as well as the resilience of these survivors who made new homes for themselves, learning new skills and creating new traditions. It also reminds us not to forget the ever-present need to provide support and aid for refugees of all nationalities, ethnicities, and religious denominations today.