B.A. Van Sise, the photojournalist whose photos of Holocaust survivors grace the Museum’s exterior and make up our Eyewitness installation, has created a new series of survivor portraits and profiles. Below is the first of these profiles.

By B.A. Van Sise

“Everybody asks me about it,” Werner Reich announces while sitting in a comfortable chair in his home. “Everyone asks how it was. I don’t know what they want me to say. Yeah, I was in Auschwitz. It was lousy.”

“Everybody asks me about it,” Werner Reich announces while sitting in a comfortable chair in his home. “Everyone asks how it was. I don’t know what they want me to say. Yeah, I was in Auschwitz. It was lousy.”

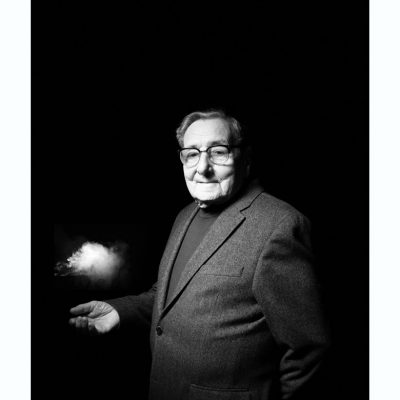

Werner is a magician. And he’s been one a long, long time: he learned his first trick there, at Auschwitz, from an older inmate who used little bits of sleight of hand to impress and curry favor with the overseers. It was a simple trick, his first trick, a little thing with cards. All magician’s first tricks are simple tricks, little things.

Survival is not simple, nor little, however, and it has been 75 years since he was freed from his concentration camp – Mauthausen, the third of his young life – as a teenager with no education, and no skills. He began his new life in England, working as a manual laborer, studying at night, learning English, attending the high school he was never offered and then the college he’d never dreamed of. English came, eventually: today he has only a thin cinematic hint of the German language that once lived inside of him. A family came, eventually – today he boasts three generations of people alive because he survived. A career came, eventually – the uneducated boy who’d been in those camps made a life, a comfortable life, in America, as an engineer.

Still, in his heart, there was a little bit of magic. He kept at it, practiced with other magicians, bought all the books he could – his shelves are still stocked thick with Tarbell’s Course of Magic, encyclopedias of tricks, plans and schematics of little wonders to dazzle and amaze. In his retirement, he keeps busy, a member of the International Brotherhood of Magicians, the Psychic Entertainers Association. And he lectures, all over the world, in schools and conference centers and hotels, on Ted Talks, possibly to anybody he meets, trying to tell the story of what happened to him with a unique magician’s flair: he uses sleight of hand, building from that first simple trick he learned so many years ago. “Nobody understands Auschwitz,” he tells me. “Everybody thinks it was like the movies. But it was fear. It was mud. It was smell. And for me, it was a magic trick.”

He elaborately demonstrates a cup and balls trick, one of his own design – an engineer, he’s built the thing himself. “I love magic,” he tells me. “I have fun with it. It keeps me off the streets.” He produces the ball from nowhere from thin air, from seventy five years of waiting, with a flourish. “Sometimes,” he giggles, “sometimes I am wonderful.”