In May of 1944, he drew an impishly happy whale breaching the surface of his graph paper, with a Star of David on its nose. A few months later, as the High Holidays approached, his imagery became more traditionally Jewish. He lettered the customary New Year’s greeting, L’shanah tovah tikatevu, on the masthead of his graph paper. Near it and to the left, covering his drawing of a shovel, he wrote in Yiddish, Gut Yomtov, and, to the right, over a drawn block of fifty kilos of cement, he wrote the same New Year’s greeting in Serbo-Croatian. He also included a menu for a delicious fantasy holiday feast, with a final course of Camel cigarettes.

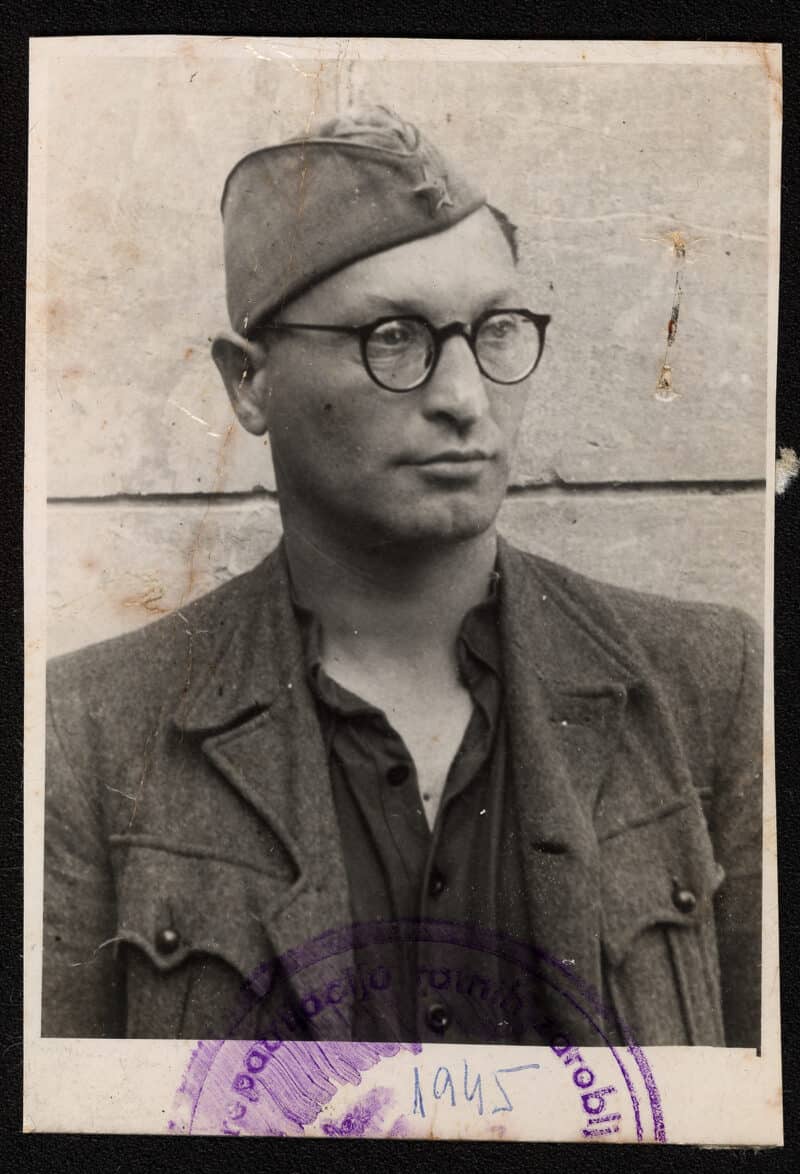

The artist was certainly no commander. He was a soldier, a Jew, and a captive of the Nazis; he was, in fact, Sergeant Major Third Class Vladimir Knezic, of the Yugoslav army, prisoner number 11212. These drawings, part of a sardonic graphic record of four years of captivity, also convey wistful good humor and a sense of Jewish identity.

Vladimir Knezic was born Vladimir Kaufman in 1909 in Zagreb, in the province of Croatia. His parents chose to change the family name to Knezic to appear more Yugoslavian in a part of the world where antisemitism was no stranger. Nevertheless, as a young child, he studied in a traditional Jewish school, a heder, and Knezic and his sister grew up in a Jewish community with strong Zionist political leanings. At age twenty, he began a career in the Yugoslav army, and during the 1930s rose through the ranks. He married a woman named Berta and they had a son, Micro.

During the political turmoil that preceded the outbreak of World War II, the Croats, the second-largest group in Yugoslavia, next to the Serbs, were agitating for their own state. In 1930, a violent, ultranationalistic organization, the Ustaše, was formed.

When the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia in April 1941, a satellite Croatian state was set up, with the Nazi-leaning Ustaše governing as puppets. By the summer of 1941, the Ustaše campaign to eliminate the Serbs and Jews had become genocidal. The Yugoslav army resisted the Germans and the Ustaše, but many units were captured, including Vladimir Knezic’s.

Mainly on foot and at times by train, the captured soldiers were sent through Macedonia, Bulgaria, and Hungary into Germany. They arrived in midsummer at a camp near Nuremberg. Conditions were extremely harsh. Yet for Jews in Zagreb, where Knezic’s family remained and about whom he knew nothing, conditions were far worse. His wife and son were likely caught up in the Ustaše’s mass arrest of Jews on June 26, 1941.

Deep inside Germany, in 1942, Vladimir Knezic could not yet know this, although he feared such an outcome. He was now part of a group of four hundred isolated Jewish prisoners of war. Serving the German war machine in Osnabrueck and other locations, they did the backbreaking and dangerous work of slave laborers—but because they were prisoners of war, the Nazis kept them alive in case they could find a way to use the POWs or exchange them.

During these years, Knezic’s drawings and cartoons became documentary and satirical, a record of his and his comrades’ lives in captivity. It was a kind of monthly news report crafted by Knezic and his friends, seen only by those they trusted. Knezic’s graphic record indicates that the POWs worked moving cement blocks and loading artillery shells onto trains. Slowly, as Allied victories mounted, conditions for the POWs, even the Jewish POWs, improved. Knezic’s news of May 1944 shows Red Cross packages from Britain, France, America, and Egypt. Radios and newspapers were allowed in September 1944. He recorded in a cartoon in March 1945 the arrival of a group of tattered soldiers, or perhaps slave laborers—Jews, in any event, recognizable by the star on their caps. They were put to work in the mine shaft of a German corporation.

Knezic was now calling himself, on the masthead of his monthly news, Kommando 2365, and would soon proclaim, in one of the final issues, “Liberte.” For in fact Vladimir Knezic was liberated in Nuremberg in April 1945. When he was released, he learned that his wife and son had been murdered in Treblinka.

Hounded by the Ustaše when he tried to return to Zagreb, Knezic went to Belgrade and worked in a Jewish orphanage; there he met a Holocaust survivor who became his wife. In 1948, they immigrated to Israel, where they raised two daughters, and that, Kommando 2365 might have agreed, was the best news of all.