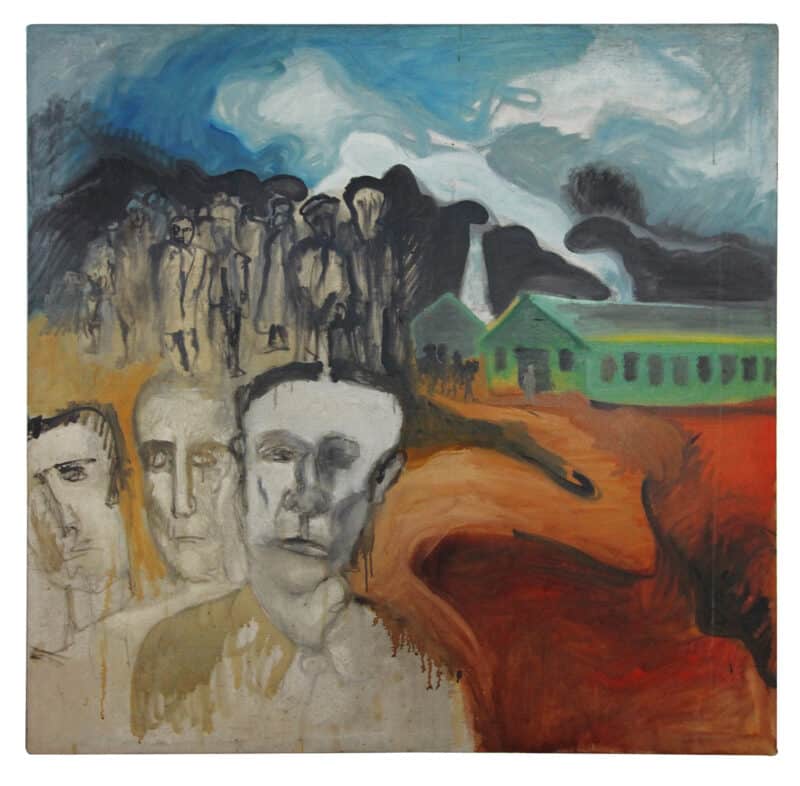

Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try is a first-of-its-kind exhibition on the 20th-century artist and Holocaust survivor Boris Lurie. Centered around his earliest work, the so-called War Series, as well as never-before-exhibited objects and ephemera from Lurie’s personal archive, the exhibition presents a portrait of an artist reckoning with devastating trauma, haunting memories, and an elusive, lifelong quest for freedom. In drawing together artistic practice and historical chronicle, Boris Lurie: Nothing To Do But To Try is fertile new territory for the Museum of Jewish Heritage, offering a survivor’s searing visual testimony within a significant art historical context.

I try my first oil painting on a plywood board. The paints are difficult to manage and very messy. I think I am doing very badly, but then I try again: maybe I am not doing so badly. …But since no one taught me anything about art, there is nothing to do but to try.” – Boris Lurie

“Nothing to do but to try” are words from Lurie’s own memoir, exemplifying the eternal quests of his life and his art: to survive as the ultimate act of creation, and to create as the ultimate act of survival.

“This exhibition deserves serious attention from the art world because the issues it foregrounds have been much discussed by many artists.” – hyperallergic.com

Explore some of Lurie’s “War Series” works and personal objects in the slideshow below.

Boris Lurie's Early Life

Boris Lurie (1924–2008) was born in Leningrad, Russia, in 1924. He was the third and youngest child of Shaina, a sharp and sophisticated dentist, and Ilya, a successful and daring businessman. As the USSR grew increasingly intolerant of capitalist activity, the family fled to then-free Latvia. They settled in Riga before Boris was two, where Boris grew up in a cosmopolitan Jewish family in Riga, Latvia. The Nazi occupation began when he was 16.

Six weeks after imprisoning the family in a ghetto, the Nazis and auxiliary Latvian officers massacred the artist’s grandmother, mother, sister, and girlfriend with approximately 25,000 other Jews in the Rumbula forest. Lurie and his father survived the rest of the war in a series of labor and concentration camps.

In 1946, Lurie immigrated to New York, where, for many years following the war, survivors were all but silenced. Barely 22, Lurie endeavored to become an artist.

The Nazis Arrive in Riga

Latvia gained independence from the Russian Empire in 1918 with Riga as its capital city and center of culture. The city flourished in the 1920s and 1930s but in 1940, Latvia was occupied and annexed by the Soviets.

The Nazis arrived in July 1941. By October, the Luries were forced out of their apartment and were interned in a newly established ghetto.

In November, the SS announced that “evacuations” were imminent. Because Boris and his father Ilya, as able-bodied men, were eligible to enter the ghetto's separate, newly established work camp, Lurie's mother Shaina made the wrenching decision to separate the family.

After a final supper together, Boris and Ilya left what had briefly become their family home. Within the week, the Nazi Einsatzgruppen [Mobile Killing Units] and a commando of Latvian officers had marched 25,000 women, children, older and disabled people to the Rumbula forest, stripped them naked, shot them, and left them in mass graves.

Among those murdered in the Rumbula massacre were Boris's grandmother, his mother Shaina, his beloved sister Jeanna, and his girlfriend Ljuba.

After Riga, 1943 - 1945

From the Riga Ghetto, Ilya and Boris were enslaved nearby at Lenta, a factory producing luxury goods for the Nazi Elite, for over a year. Under supervision of the relatively lenient Fritz Scherwitz (the so-called “Jewish SS officer”), Boris described Lenta as an “island in a sea of horror.”

The Nazis dissolved Lenta in 1944, as the Russian army advanced. Boris and Ilya were briefly interned at the Salaspils concentration camp, in Latvia, then sent by hellish boat passage to the Stutthof camp in modern-day Poland. In November 1944, they were sent as skilled laborers to Magdeburg, a satellite camp of Buchenwald with more humane living conditions.

In April 1945, with the Allies closing in, the Nazis evacuated Magdeburg in a forced march. Boris escaped, hiding in the attic of a bombed-out building and narrowly avoiding re-capture until the Americans officially liberated Magdeburg a week later. Boris walked back—free and exhilarated—to look for his father. When he reached the camp, Boris fell into a days-long fever sleep, awakening to find Ilya at his side.